It's interesting, the synchronicity of the topic and my work this week. In the course of preparing for our Open House on Saturday, I was invited to select one book to recommend to readers as well as a 5-book package for our silent auction.

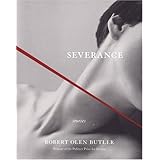

For my pick for readers, I chose Robert Olen Butler's Severance, a book I wish he hadn't written because I would have liked to write it. Butler writes in the voices of history's most famous severed heads. While the voices themselves are compelling and unique (and numerous!), what I really envy about this book is how Butler calculated the likely number of words the human brain can process from the moment of beheading until loss of consciousness--and then wrote these little pieces using that number of words. I love the constriction of form, and I also love obsession. This book hits all my buttons.

For my auction selections, I chose poets whose voices are also unique, distinctive, and important:

Sandra Beasley's Theories of Falling

Robin Becker's The Horse Fair

Richard Blanco's City of a Hundred Fires

Carolyn Forché's The Country Between Us

Belle Waring's Dark Blonde

Of these, consider Forché's poem "The Colonel," which details an event from El Salvador during its violent civil war:

The Colonel

What you have heard is true. I was in his house. His wife carried a tray of coffee and sugar. His daughter filed her nails, his son went out for the night. There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the cushion beside him. The moon swung bare on

its black cord over the house. On the television was a cop show. It was in English. Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to scoop the kneecaps from a man's legs or cut his hands to lace. On the windows there were gratings

like those in liquor stores. We had dinner, rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell was on the table for calling the maid. The maid brought green mangoes, salt, a type of bread. I was asked how I enjoyed the country. There was a brief commercial in

Spanish. His wife took everything away. There was some talk of how difficult it had become to govern. The parrot said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say

nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries home. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around he said. As for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go f--- themselves. He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last of his wine in the air. Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

The voice here is horrified, as we are reading of the event, yet the detachment, the attention to details, are lyric and scattered, the way we tend to remember traumatic or frightening events. Forché's austerity, her lack of judgment of both the speaker and the characters within the poem, allow her images to do the work another voice might do through rhetoric. This is truly a remarkable poem, one I return to again and again in my own reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment