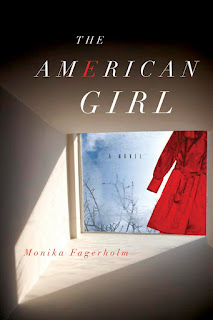

The American Girl

by Monika Fagerholm

Other Press

Released February 2010

507 pages

Reviewed by Kyle Semmel

In recent years, Scandinavian writers have provided readers around the globe with some interesting novels—novels that, to the overwhelming delight of their publishers, also happen to sell tons of books. Names like Per Petterson (Norway), Henning Mankell (Sweden), and Stieg Larsson (Sweden) come to mind. Go to Stockholm and you can even take a tour of Larsson's "fictional" city. But with the booming worldwide popularity of especially Mankell's and Larsson's detective fiction, the question arises: Is there room for other, less traditional Scandinavian voices to break through in the United States?

That's a question Finnish author Monika Fagerholm's newly released novel The American Girl may soon answer. Widely acclaimed in Europe, Fagerholm, who is part of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland, is not yet a household name in the United States. Though her novel Wonderful Women by the Sea (1997) was published in the U.S. and was even shortlisted for the prestigious International IMPAC Literary Award, it's The American Girl and next year's sequel, The End of the Glitter Scene (which has been nominated for Scandinavia's most important literary award, the Nordic Council Literature Prize, and will also be published in English by Other Press), that may truly bring her widespread American recognition.

Or not.

Like many popular Scandinavian novels to reach these shores, The American Girl uses some elements of the mystery genre in its genetic coding. But let me be clear at the outset: this is a book that defies convention and is difficult to categorize. If you think you're picking up a quick, easy beach read—if you think you're picking up a novel modeled on Mankell—well, you're absolutely, definitely not.

At the book's start, the American girl, Eddie de Wire, has drowned in a marsh in the "district," a region near Helsinki populated with some fairly strange, insular characters, and Eddie rapidly becomes part of local lore. Enter Sandra Wärn, Sandra's father—referred to as the Islander—and Sandra's mother, Lorelei Lindberg. They move into the large, mysterious house the Islander builds for Lorelei in the district—"the house in the darker part of the woods." One day Sandra finds a lone girl, Doris Flinkenberg, sleeping at the bottom of their empty swimming pool. Like Sandra, Doris is an odd girl with a troubled past, and Sandra knows that it was "the right time for the first meeting, one of the most important meetings in Sandra's entire life."

This meeting marks the beginning of the girls' friendship--a friendship that serves as the driving force of the novel. Though The American Girl toggles back and forth between characters and scenes—and does so in a way that will challenge you at times—the novel is, ultimately, their story. They are smart, imaginative girls attracted to solving the mystery surrounding Eddie de Wire's death, and together they form a deep bond that is only severed by a tragedy involving one of the girls.

The American Girl is, at its core, not a mystery but a coming-of-age story, a kind of YA novel for grownups, combining the breathless immediacy of young adult literature with the darker knowledge of adulthood you find in, say, the best of Joyce Carol Oates' novels. To be sure, this book is decidedly not a young adult novel. Far from it. It is a sprawling, slowly unraveling narrative that would probably be a slog for young readers. For adults, however, there's much to appreciate. But it remains to be seen if it can generate the kind of hyper-buzz that recent Scandinavian novels have generated here. Still, Monika Fagerholm's is a unique voice that deserves a wider readership.

And with translator Katarina E. Tucker, a past winner of the American-Scandinavian Foundation Translation Prize, her work gets a loving and faithful touch. American readers who prize the pleasure in a good novel told slowly, who chew thoughtfully on the language and the structure of stories told unconventionally, may find in The American Girl a rare treat—to be continued next year in the sequel.

***

Kyle Semmel is the publications and communications manager of The Writer's Center and administrator of First Person Plural. In addition to his work at TWC, he is a writer and translator (under the name K.E. Semmel) whose work has appeared in Ontario Review, The Washington Post, Aufgabe, The Brooklyn Review, The Bitter Oleander, Redivider, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and elsewhere. His translation of Jytte Borberg's classic Danish story "Englene" will soon appear as "Angels" in The New Renaissance. His interview with internationally acclaimed poet Pia Tafdrup is in the current issue of World Literature Today. For his translations of Simon Fruelund’s fiction, he received a translation grant from the Danish Arts Council.

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Friday, February 26, 2010

Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series, American Ensemble Theatre, and More

Tonight is American Ensemble Theater's FREE staged reading of Larry Shue's Wenceslas Square, directed by Krista Cowan. This admission-free series is co-sponsored by The Writer's Center. Workshop leader Martin Blank is a co-founder of this theater. You can read a nice write-up in The Washington Post from earlier this week here. The story is in the same article with one of our Bethesda friends Round House Theatre. The event begins at 7:30 p.m. in the Jane Fox Reading Room.

About the Play:

In Larry Shue's dark comedy, an American professor and his student find themselves in danger as they struggle to discover what happened to the rebellious Czech theater movement. Visit their Web site at http://www.americanensemble.org/

Workshop Leader Rose Solari

Rose Solari's poem, "Math & the Garden," will appear in the anthology, Initiate: An Oxford Anthology of New Writing, forthcoming from Oxford University Press and Blackwell Books in November, 2010. In June, Rose will lead a seminar at Oxford's Kellogg College Creative Writing Series, entitled, Divided by a Common Language: Divergent Paths in British and American Poetry. Unfortunately for those here in the DC area, Rose's A Sense of the Whole workshop has already begun.

Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series

Thanks to Deborah Ager of 32 Poems for sharing this news with me. D.C. area poets wanted:

It's time to apply to the the Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series.

It takes place Tuesdays at 7:30 p.m. in Rock Creek Park, Picnic Area Number 6, during June and July. Two poets are usually featured, reading their original poetry.

TO APPLY to the series, send the following:

5 poems, typed, one poem per page. No one poem longer than two pages.

Name, address, telephone numbers, email on first page of the submission. Name on every page.

Brief biographical note, including publications, readings, literary studies, prizes.

Stamped, self-addressed envelope for reply (for return of poems, add sufficient postage as needed).

NOTE: All manuscripts must be typed. Any form or style of poetry will be considered; selection is made on the basis of the poems submitted. The biographical note is for information only. The director is assisted by a panel of writers in choosing poets.

SEND TO:

Rosemary Winslow , Co-Director

Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series

Department of English

The Catholic University of America

Washington, DC 20064

DEADLINE: Postmarked on or before March 31 of each year.

IF SELECTED, you will read your work at the cabin and receive a small honorarium. If you have books published, you may sell them at the reception. If you live out of town, need a place to stay, an effort is made to provide lodging by the director and Word Works staff.

Pia Tafdrup

And finally, if you're so inclined, my interview with internationally acclaimed Danish poet Pia Tafdrup appears in the new issue of World Literature Today. By the by, there might just be some big news in the offing regarding international writers and TWC. Stay tuned for that!

Kyle

About the Play:

In Larry Shue's dark comedy, an American professor and his student find themselves in danger as they struggle to discover what happened to the rebellious Czech theater movement. Visit their Web site at http://www.americanensemble.org/

Workshop Leader Rose Solari

Rose Solari's poem, "Math & the Garden," will appear in the anthology, Initiate: An Oxford Anthology of New Writing, forthcoming from Oxford University Press and Blackwell Books in November, 2010. In June, Rose will lead a seminar at Oxford's Kellogg College Creative Writing Series, entitled, Divided by a Common Language: Divergent Paths in British and American Poetry. Unfortunately for those here in the DC area, Rose's A Sense of the Whole workshop has already begun.

Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series

Thanks to Deborah Ager of 32 Poems for sharing this news with me. D.C. area poets wanted:

It's time to apply to the the Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series.

It takes place Tuesdays at 7:30 p.m. in Rock Creek Park, Picnic Area Number 6, during June and July. Two poets are usually featured, reading their original poetry.

TO APPLY to the series, send the following:

5 poems, typed, one poem per page. No one poem longer than two pages.

Name, address, telephone numbers, email on first page of the submission. Name on every page.

Brief biographical note, including publications, readings, literary studies, prizes.

Stamped, self-addressed envelope for reply (for return of poems, add sufficient postage as needed).

NOTE: All manuscripts must be typed. Any form or style of poetry will be considered; selection is made on the basis of the poems submitted. The biographical note is for information only. The director is assisted by a panel of writers in choosing poets.

SEND TO:

Rosemary Winslow , Co-Director

Joaquin Miller Cabin Poetry Series

Department of English

The Catholic University of America

Washington, DC 20064

DEADLINE: Postmarked on or before March 31 of each year.

IF SELECTED, you will read your work at the cabin and receive a small honorarium. If you have books published, you may sell them at the reception. If you live out of town, need a place to stay, an effort is made to provide lodging by the director and Word Works staff.

Pia Tafdrup

And finally, if you're so inclined, my interview with internationally acclaimed Danish poet Pia Tafdrup appears in the new issue of World Literature Today. By the by, there might just be some big news in the offing regarding international writers and TWC. Stay tuned for that!

Kyle

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Amy Dawson Robertson on Publishing Her First Novel: Miles to Go

Member Amy Dawson Robertson is a native Virginian and graduated from St. John’s College in Annapolis. She lives in the Washington DC area and her writing interests include genre fiction, short stories, and graphic novels. She creates strong female characters in action-packed stories drawn on current events. Here she is on getting started writing and publishing her first novel, Miles to Go. Find her online here.

Though my early writing interests tended more toward literary fiction, I knew that I needed a better understanding of the basic mechanics of fiction. Unfortunately, I hadn’t heard about The Writer's Center yet. As a kind of self-directed workshop I decided to write a genre novel. I figured that a plot-centric work would be the ideal vehicle for learning to handle point of view, description, dialogue – all of the fundamentals. It turned out that I was engaged by both my characters and my plot and worked the novel until it was in the best shape I could make it. I thought, Why not try to sell it?

At first, I went the traditional route of sending off query letters to agents. Much too easily discouraged after a few form letter rejections, I contacted The Writer's Center for help on my query letter and synopsis. Working with Barbara Esstman and Noreen Wald improved my submission package dramatically. Unfortunately, I was still unable to gain representation (though I admit giving up fairly quickly). Becoming more aware of the publishing market, I understood that my novel, an action thriller with a gay heroine, was not going to be picked up by a mainstream publisher. So I focused on submitting directly to small presses known to publish gay genre fiction. That did the trick. In November 2008, Bella Books contracted Miles To Go, the first in The Rennie Vogel Intrigue series. The book was released this month.

There are many pluses to working with a small publisher. I was lucky to have Katherine V. Forrest – a true icon in the genre – as my editor. Writing in a niche genre brings with it a very dedicated built-in audience who are hungry for new titles. And it doesn’t hurt that I am actually in a niche within the niche since the predominance of titles are romances and mine is an espionage style thriller.

These days publishers – small and large – are putting less and less money into promoting an author’s work. A small fraction of books and authors are still heavily touted but the rest of us, especially those of us at small presses, are left to fight for attention in a media saturated world. But what opportunity there is now for direct marketing! I am on Facebook, Goodreads, Library Thing, Filedby, Shelfari, She Writes, Yahoo Groups, Delicious – the list of social networking opportunities is seemingly endless. Now if only they weren’t so time consuming that I could sit down and write that next book...

Though I still crave to write the perfect short story, I am having fun with my thriller series. And who knows? It may just turn out that it’s where my strength lies. I would recommend that writers trying to sell their first novel should investigate where it best fits into the market and then develop their pitch strategy from there.

Though my early writing interests tended more toward literary fiction, I knew that I needed a better understanding of the basic mechanics of fiction. Unfortunately, I hadn’t heard about The Writer's Center yet. As a kind of self-directed workshop I decided to write a genre novel. I figured that a plot-centric work would be the ideal vehicle for learning to handle point of view, description, dialogue – all of the fundamentals. It turned out that I was engaged by both my characters and my plot and worked the novel until it was in the best shape I could make it. I thought, Why not try to sell it?

At first, I went the traditional route of sending off query letters to agents. Much too easily discouraged after a few form letter rejections, I contacted The Writer's Center for help on my query letter and synopsis. Working with Barbara Esstman and Noreen Wald improved my submission package dramatically. Unfortunately, I was still unable to gain representation (though I admit giving up fairly quickly). Becoming more aware of the publishing market, I understood that my novel, an action thriller with a gay heroine, was not going to be picked up by a mainstream publisher. So I focused on submitting directly to small presses known to publish gay genre fiction. That did the trick. In November 2008, Bella Books contracted Miles To Go, the first in The Rennie Vogel Intrigue series. The book was released this month.

There are many pluses to working with a small publisher. I was lucky to have Katherine V. Forrest – a true icon in the genre – as my editor. Writing in a niche genre brings with it a very dedicated built-in audience who are hungry for new titles. And it doesn’t hurt that I am actually in a niche within the niche since the predominance of titles are romances and mine is an espionage style thriller.

These days publishers – small and large – are putting less and less money into promoting an author’s work. A small fraction of books and authors are still heavily touted but the rest of us, especially those of us at small presses, are left to fight for attention in a media saturated world. But what opportunity there is now for direct marketing! I am on Facebook, Goodreads, Library Thing, Filedby, Shelfari, She Writes, Yahoo Groups, Delicious – the list of social networking opportunities is seemingly endless. Now if only they weren’t so time consuming that I could sit down and write that next book...

Though I still crave to write the perfect short story, I am having fun with my thriller series. And who knows? It may just turn out that it’s where my strength lies. I would recommend that writers trying to sell their first novel should investigate where it best fits into the market and then develop their pitch strategy from there.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

Keep Poetry Sacred: An Interview with Dora Malech

At our Sunday, March 7 Open Door Reading at The Writer's Center, Dora Malech--a Bethesda native and former workshop participant--will join one of our current workshop leaders, Nancy Noami Carlson, for what will be a great, great poetry reading. Here's an interview I recently conducted with Dora. But first, here's Dora's bio:

Dora Malech was born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1981 and grew up in Bethesda, Maryland. She earned a BA in Fine Arts from Yale College in 2003 and an MFA in Poetry from the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2005. She has been the recipient of a Frederick M. Clapp Poetry Writing Fellowship from Yale, a Truman Capote Fellowship and a Teaching-Writing Fellowship from the Writers’ Workshop, a Glenn Schaeffer Poetry Award, and a Writer’s Fellowship at the Civitella Ranieri Center in Umbertide, Italy. The Waywiser Press published her first full-length collection of poems, Shore Ordered Ocean, in 2009. The Cleveland State University Poetry Center will publish her second collection, Say So, in late 2010. Her poems have appeared in numerous publications, including The New Yorker, Poetry, Best New Poets, American Letters & Commentary, Poetry London, and The Yale Review. She has taught writing at the University of Iowa; Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters in Wellington, New Zealand; Kirkwood Community College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa; and Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois. In Fall 2010, she will serve as Distinguished Writer-in-Residence in Poetry for the MFA Creative Writing Program at Saint Mary’s College of California. Her paintings and drawings are represented by The Chait Galleries in Iowa City, Iowa, where she lives. Find her online at doramalech.com.

Kyle Semmel: Before I ask about Shore Ordered Ocean, I want to know when you took your workshop(s) at The Writer's Center? Who was your workshop leader(s)?

Dora Malech: I must have “discovered” The Writer’s Center in the mid-nineties, in late junior high school or early high school. My family went to the Chinese restaurant (it used to be called Peking Hunan, but it’s Moongate now) at the other end of the big parking lot from TWC, and when I saw The Writer’s Center, it felt like destiny. Keep in mind that I was fourteen or fifteen years old, and thus prone to interior drama and believing in destiny whenever possible. That said, it truly was exciting to open the doors and discover a place where people were making a life out of what I loved to do, which was write.

I remember the coffee-and-photocopier smell; I remember flipping through the literary magazines and reading contemporary poetry for the first time, really. I bought a copy of Hayden’s Ferry Review and pored over it and eventually ripped out a poem by Jon Pineda that I held onto for years.

I ended up taking a Summer workshop with Rose Solari, and then a Fall workshop with Rose Solari, and so on. In short, I fell in love. Rose was a passionate, sensitive, intelligent, no-nonsense workshop leader. I remember her as being reverent when it came to poetry and irreverent when it came to everything else. I bought her collection of poems, Difficult Weather, and carried it with me everywhere. I underlined and dog-eared and asterixed it up. She was like the high priestess of poetry to me as a teenager: I worshiped the way she carried herself in the world and the way she carried herself on the page. In her presence, poetry was no longer a lofty abstraction; it was a life.

KS: How did your experience at TWC help prepare you for future writing workshops--at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, for example?

DM: Being in writing workshops at TWC, as opposed to English classes at school, taught me to read as a poet, to tune into language and form and image and so forth, as opposed to trying to hack past the language to critique the so-called content. I learned to share my reactions without being proscriptive; I learned that asking good questions is usually more helpful than trying to sound smart; I learned to take criticism and I learned the importance of rigorous revision. I also learned, however, that different writers have different visions of what a poem should “do”, of what a poem “is”, and that we should value that diversity instead of trying to homogenize. Internalizing those lessons at TWC enabled me to be a more constructive workshop participant and, eventually, a more constructive workshop leader.

KS: You've had a lot of success in your career. What would your advice be to young poets who aim to make a life out of writing, reading, and teaching poetry?

Oh, boy. My first impulse when I see the words “success” and “career” is to start self-denigrating, to list the publications that have rejected me, to admit to the great literature that I still haven’t thoroughly read and absorbed, to rail against the adjunct system in American colleges that leaves so many of us underemployed, or benefit-less, or unsure if we’ll have a job from year to year or term to term. That, however, is just my first impulse. Then I take a deep breath, and try to take my own advice, which is the following: don’t blame poetry for the shortcomings of people/things/society. Keep poetry sacred.

Don’t let a rejection slip, or an egomaniacal workshop leader (not at TWC, of course, but they’re out there!), or a snarky blog, or a careerist prize-winner, or a rude editor get between you and the page. The only thing between you and the page is a pen or a pencil. I hope this makes sense; I guess I’m trying to say that if “po-biz” or academia or interpersonal tzurrus or apathy or small-mindedness get you down, which they will, don’t let that poison your relationship with poetry. Easier said than done, I know. But we have to try.

My other piece of advice for young poets is much simpler: read like crazy. Read it all. There are conversations happening on the page that defy time and space; when you read, you enable yourself to enter those conversations. Your world becomes richer and more complicated, and your writing follows.

KS: The poems "Makeup" and "S.O.S."--which, along with many other poems in this collection, explore death--are immediately followed up by a wonderful "birth" poem called "Delivery Rhyme." Can you talk about the writing and the structure of Shore Ordered Ocean? How did you go about putting these poems together?

The book came together much like my poems come together: I don’t force a “theme” or “subject” when I’m generating a poem; I’m more like a hunter-gatherer than a farmer who can cultivate a particular crop. I do, however, eventually step back and look for patterns and threads, rearranging for juxtapositions and maximizing discourse between images and moments of language. With Shore Ordered Ocean, I had a big muddle of individual poems and I tried to let them talk to each other, literally spreading them out on the floor, shuffling and reshuffling. They talked to each other about love and death and family and relationships and war and distance… all kinds of distance. I wrote the poems during a time when I was trying to navigate different kinds of distance: the frustration of being a citizen of a country at war when the media mediates all of the horrors of that war for me; the more straight-forward physical remove of a long-distance relationship. I tried to weave these, and other, distances together to create not a narrative exactly, but perhaps a trajectory or momentum through the collection. I think about that Dylan Thomas line, “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower”; I hope that that “force” is present in the collection, even if I can’t exactly explain it. I hope there’s at least some resonance, or friction, when birth and death or love and war rub elbows from poem to poem, and within poems as well.

KS: I'm curious about "The Numbers Game." How did you come to write a poem consisting solely of surnames of U.S. soldiers killed in Iraq?

When I wrote that poem, I was thinking a lot about the war in Iraq; I was living in New Zealand, so I felt doubly removed from what was being done in the name of my country. I watched the war from a distance, and the Bush administration from a distance, and America from a distance. I struggled with how to make the images and events in newspapers and on television real to me, and then I struggled with my own lack of agency. What did I think my individual empathy could accomplish? I didn’t have an answer and still don’t.

“The Numbers Game” is actually kind of a companion piece to the poem that precedes it in Shore Ordered Ocean, “O-Dark-Hundred”, in which I explore the aforementioned frustrations and doubts. I finished venting in that poem, and obviously, the dead remained. We can’t will them back (or will them away). Mission never accomplished. I felt like my usual “materials” (images, syntax, etcetera) were inadequate, so I just let the names speak for themselves.

Reading the names of the dead aloud is certainly not my own idea; every year, on Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, we read the names of the dead. There are readings of the names of service-people who died in Vietnam. There are readings of the names of individuals who have died of AIDS. There is something incantatory about saying those names, even if the incantation can’t possibly “do” what we might hope it could.

KS: This summer, coming full circle, so to speak, you'll be teaching at the prestigious Iowa Writers' Workshop. Can you tell us about your philosophy of creative writing teaching? What can your students expect?

I’ll be teaching an eight-week Graduate Summer Poetry Workshop through the Iowa Writers’ Workshop; usually the Workshop’s courses are open to graduate students only, but undergraduates and non-students can also apply for this summer course. I’ll also be teaching a few workshops through the Iowa Summer Writing Festival. I believe in a balance of rigor and nurture in a workshop; a workshop should be a place to take risks and explore new possibilities, to get out of your comfort zone. Of course, to enable participants to take those risks, there has to be a supportive atmosphere and a constructive classroom community. I think that a workshop leader has a responsibility to strive to establish that balance right away, although the participants themselves are ultimately responsible for their own community as well. I try hard to get the ball rolling and then park my ego, allowing my voice to be one of many voices in the room. I think a good workshop requires energy on everyone’s part, but a good workshop also creates energy that propels and informs its participants’ writing even after the workshop itself is over. I’m getting excited already!

Dora Malech was born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1981 and grew up in Bethesda, Maryland. She earned a BA in Fine Arts from Yale College in 2003 and an MFA in Poetry from the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2005. She has been the recipient of a Frederick M. Clapp Poetry Writing Fellowship from Yale, a Truman Capote Fellowship and a Teaching-Writing Fellowship from the Writers’ Workshop, a Glenn Schaeffer Poetry Award, and a Writer’s Fellowship at the Civitella Ranieri Center in Umbertide, Italy. The Waywiser Press published her first full-length collection of poems, Shore Ordered Ocean, in 2009. The Cleveland State University Poetry Center will publish her second collection, Say So, in late 2010. Her poems have appeared in numerous publications, including The New Yorker, Poetry, Best New Poets, American Letters & Commentary, Poetry London, and The Yale Review. She has taught writing at the University of Iowa; Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters in Wellington, New Zealand; Kirkwood Community College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa; and Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois. In Fall 2010, she will serve as Distinguished Writer-in-Residence in Poetry for the MFA Creative Writing Program at Saint Mary’s College of California. Her paintings and drawings are represented by The Chait Galleries in Iowa City, Iowa, where she lives. Find her online at doramalech.com.

Kyle Semmel: Before I ask about Shore Ordered Ocean, I want to know when you took your workshop(s) at The Writer's Center? Who was your workshop leader(s)?

Dora Malech: I must have “discovered” The Writer’s Center in the mid-nineties, in late junior high school or early high school. My family went to the Chinese restaurant (it used to be called Peking Hunan, but it’s Moongate now) at the other end of the big parking lot from TWC, and when I saw The Writer’s Center, it felt like destiny. Keep in mind that I was fourteen or fifteen years old, and thus prone to interior drama and believing in destiny whenever possible. That said, it truly was exciting to open the doors and discover a place where people were making a life out of what I loved to do, which was write.

I remember the coffee-and-photocopier smell; I remember flipping through the literary magazines and reading contemporary poetry for the first time, really. I bought a copy of Hayden’s Ferry Review and pored over it and eventually ripped out a poem by Jon Pineda that I held onto for years.

I ended up taking a Summer workshop with Rose Solari, and then a Fall workshop with Rose Solari, and so on. In short, I fell in love. Rose was a passionate, sensitive, intelligent, no-nonsense workshop leader. I remember her as being reverent when it came to poetry and irreverent when it came to everything else. I bought her collection of poems, Difficult Weather, and carried it with me everywhere. I underlined and dog-eared and asterixed it up. She was like the high priestess of poetry to me as a teenager: I worshiped the way she carried herself in the world and the way she carried herself on the page. In her presence, poetry was no longer a lofty abstraction; it was a life.

KS: How did your experience at TWC help prepare you for future writing workshops--at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, for example?

DM: Being in writing workshops at TWC, as opposed to English classes at school, taught me to read as a poet, to tune into language and form and image and so forth, as opposed to trying to hack past the language to critique the so-called content. I learned to share my reactions without being proscriptive; I learned that asking good questions is usually more helpful than trying to sound smart; I learned to take criticism and I learned the importance of rigorous revision. I also learned, however, that different writers have different visions of what a poem should “do”, of what a poem “is”, and that we should value that diversity instead of trying to homogenize. Internalizing those lessons at TWC enabled me to be a more constructive workshop participant and, eventually, a more constructive workshop leader.

KS: You've had a lot of success in your career. What would your advice be to young poets who aim to make a life out of writing, reading, and teaching poetry?

Oh, boy. My first impulse when I see the words “success” and “career” is to start self-denigrating, to list the publications that have rejected me, to admit to the great literature that I still haven’t thoroughly read and absorbed, to rail against the adjunct system in American colleges that leaves so many of us underemployed, or benefit-less, or unsure if we’ll have a job from year to year or term to term. That, however, is just my first impulse. Then I take a deep breath, and try to take my own advice, which is the following: don’t blame poetry for the shortcomings of people/things/society. Keep poetry sacred.

Don’t let a rejection slip, or an egomaniacal workshop leader (not at TWC, of course, but they’re out there!), or a snarky blog, or a careerist prize-winner, or a rude editor get between you and the page. The only thing between you and the page is a pen or a pencil. I hope this makes sense; I guess I’m trying to say that if “po-biz” or academia or interpersonal tzurrus or apathy or small-mindedness get you down, which they will, don’t let that poison your relationship with poetry. Easier said than done, I know. But we have to try.

My other piece of advice for young poets is much simpler: read like crazy. Read it all. There are conversations happening on the page that defy time and space; when you read, you enable yourself to enter those conversations. Your world becomes richer and more complicated, and your writing follows.

KS: The poems "Makeup" and "S.O.S."--which, along with many other poems in this collection, explore death--are immediately followed up by a wonderful "birth" poem called "Delivery Rhyme." Can you talk about the writing and the structure of Shore Ordered Ocean? How did you go about putting these poems together?

The book came together much like my poems come together: I don’t force a “theme” or “subject” when I’m generating a poem; I’m more like a hunter-gatherer than a farmer who can cultivate a particular crop. I do, however, eventually step back and look for patterns and threads, rearranging for juxtapositions and maximizing discourse between images and moments of language. With Shore Ordered Ocean, I had a big muddle of individual poems and I tried to let them talk to each other, literally spreading them out on the floor, shuffling and reshuffling. They talked to each other about love and death and family and relationships and war and distance… all kinds of distance. I wrote the poems during a time when I was trying to navigate different kinds of distance: the frustration of being a citizen of a country at war when the media mediates all of the horrors of that war for me; the more straight-forward physical remove of a long-distance relationship. I tried to weave these, and other, distances together to create not a narrative exactly, but perhaps a trajectory or momentum through the collection. I think about that Dylan Thomas line, “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower”; I hope that that “force” is present in the collection, even if I can’t exactly explain it. I hope there’s at least some resonance, or friction, when birth and death or love and war rub elbows from poem to poem, and within poems as well.

KS: I'm curious about "The Numbers Game." How did you come to write a poem consisting solely of surnames of U.S. soldiers killed in Iraq?

When I wrote that poem, I was thinking a lot about the war in Iraq; I was living in New Zealand, so I felt doubly removed from what was being done in the name of my country. I watched the war from a distance, and the Bush administration from a distance, and America from a distance. I struggled with how to make the images and events in newspapers and on television real to me, and then I struggled with my own lack of agency. What did I think my individual empathy could accomplish? I didn’t have an answer and still don’t.

“The Numbers Game” is actually kind of a companion piece to the poem that precedes it in Shore Ordered Ocean, “O-Dark-Hundred”, in which I explore the aforementioned frustrations and doubts. I finished venting in that poem, and obviously, the dead remained. We can’t will them back (or will them away). Mission never accomplished. I felt like my usual “materials” (images, syntax, etcetera) were inadequate, so I just let the names speak for themselves.

Reading the names of the dead aloud is certainly not my own idea; every year, on Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, we read the names of the dead. There are readings of the names of service-people who died in Vietnam. There are readings of the names of individuals who have died of AIDS. There is something incantatory about saying those names, even if the incantation can’t possibly “do” what we might hope it could.

KS: This summer, coming full circle, so to speak, you'll be teaching at the prestigious Iowa Writers' Workshop. Can you tell us about your philosophy of creative writing teaching? What can your students expect?

I’ll be teaching an eight-week Graduate Summer Poetry Workshop through the Iowa Writers’ Workshop; usually the Workshop’s courses are open to graduate students only, but undergraduates and non-students can also apply for this summer course. I’ll also be teaching a few workshops through the Iowa Summer Writing Festival. I believe in a balance of rigor and nurture in a workshop; a workshop should be a place to take risks and explore new possibilities, to get out of your comfort zone. Of course, to enable participants to take those risks, there has to be a supportive atmosphere and a constructive classroom community. I think that a workshop leader has a responsibility to strive to establish that balance right away, although the participants themselves are ultimately responsible for their own community as well. I try hard to get the ball rolling and then park my ego, allowing my voice to be one of many voices in the room. I think a good workshop requires energy on everyone’s part, but a good workshop also creates energy that propels and informs its participants’ writing even after the workshop itself is over. I’m getting excited already!

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

MyNeighborsNetwork

The Writer's Center has formed a partnership with myNeighborsNetwork. TWC members can get free memberships to this unique service (please read below to find out just what you can get). If you're interested in getting your free membership, use the code below. Once you register, we'll just check to make sure your TWC membership is up to date. The following was written by MyNeighborsNetwork founder Sharon Rainey:

It can be tiresome always having to find someone to ask about who they recommend for painting or HVAC help. And it can be even more difficult to find out which dentist or ob-gyn a trusted friend goes to. In a pinch, like a few weeks ago, just finding a snow removal company was a challenge for many!

myNeighborsNetwork offers you more than 10,000 referrals from your neighbors (with their names attached) for the above professions and much, much more; everything from acupuncturists, pediatricians, and yoga instructors.

myNeighborsNetwork also offers community announcements and the latest police and fire information. Our members have notified the network with bank robberies, electrical outages, and road closures.

And one of our favorite sections of the site is the Lost & Found Animals, ranging from the classic cats and dogs, but also including horses, parrots.

We are also fortunate to have participated in the successful find of two missing children.

We have been in the D.C. Metro area since 2003, growing through grass roots referrals of super-satisfied members. Our renewal rate is 85%.

myNeighborsNetwork operates in Montgomery, Fairfax, and Loudoun Counties. Sign up today for a free year’s membership to the communities you want to be involved in. There is no catch; you may cancel at any time. Simply enter WC12 in the Gift Code when you sign up. You will be asked for a credit card number (yes, we are a secure site), but the card is NOT charged.

Questions? Feel free to call 703-759-2102. We are happy to help. Take advantage of this wonderful FREE offer and see what YOUR neighbors are talking about! http://www.myneighborsnetwork.com/.

It can be tiresome always having to find someone to ask about who they recommend for painting or HVAC help. And it can be even more difficult to find out which dentist or ob-gyn a trusted friend goes to. In a pinch, like a few weeks ago, just finding a snow removal company was a challenge for many!

myNeighborsNetwork offers you more than 10,000 referrals from your neighbors (with their names attached) for the above professions and much, much more; everything from acupuncturists, pediatricians, and yoga instructors.

myNeighborsNetwork also offers community announcements and the latest police and fire information. Our members have notified the network with bank robberies, electrical outages, and road closures.

And one of our favorite sections of the site is the Lost & Found Animals, ranging from the classic cats and dogs, but also including horses, parrots.

We are also fortunate to have participated in the successful find of two missing children.

We have been in the D.C. Metro area since 2003, growing through grass roots referrals of super-satisfied members. Our renewal rate is 85%.

myNeighborsNetwork operates in Montgomery, Fairfax, and Loudoun Counties. Sign up today for a free year’s membership to the communities you want to be involved in. There is no catch; you may cancel at any time. Simply enter WC12 in the Gift Code when you sign up. You will be asked for a credit card number (yes, we are a secure site), but the card is NOT charged.

Questions? Feel free to call 703-759-2102. We are happy to help. Take advantage of this wonderful FREE offer and see what YOUR neighbors are talking about! http://www.myneighborsnetwork.com/.

Sunday, February 21, 2010

Review Monday: The Museum of Eterna's Novel (The First Good Novel)

Macedonio Fernández

The Museum of Eterna’s Novel (The First Good Novel)

(translated from the Spanish by Margaret Schwartz) with a foreword by Adam Thirwell.

Open Letter

Pub Date: February 23, 2010

Reviewed by Luis Alberto Ambroggio

In this extraordinary literary creation, Borges’ mentor, Macedonio Fernández, masters in the reader's playful engagement to games of the word and of the mind beyond literature and metaphysics. One of the great Argentine writers of the twentieth century, Macedonio (as he preferred to be called), wrote this novel (or anti-novel) with an originality and perversity second to none—way ahead of his time and beyond the avant-guard rupture with previous conventions. He redefined the genre and influenced the great literary geniuses among Hispanic-American writers, including Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, Ricardo Piglia, and many others.

“Whoever preceded him might shine in history," Borges wrote, "but they were all rough drafts of Macedonio, imperfect previous versions. To not imitate this canon would have represented incredible negligence.”

The Museum of Eterna’s Novel (The First Good Novel) is structured as a challenge to realism, to logic, and to structure itself, as if the author intended to demolish the sense of fluidity of a normal novel and its aesthetic tendency towards realism and the solemnity of style. Instead, we (the readers) are forced (as well as intelectually seduced) to immerse ourselves in continual digressions and discussions on the roles of authors, readers, critics, characters, theories on genres, etc., as if these topics were objects which are acquired and kept in a Museum. This Museum is also, as Adam Thirlwell writes in the foreword, a “laboratory for investigating whether every philosophical question can be observed through the condition of falling in love.”

Museum starts by offering over 50 prologues with a wide range of themes: mortality and eternity; perspective and the viscitudes of the author (including authorial despair); critics; context; non-existence; and so on. Many of these themes have digressions containing dedications, salutations, and narratives on whether readers should accept or reject a chracter in an elaborate effort to playfully frustrate and challenge.

Following the prologues are twenty chapters concerning a group of characters (some borrowed from other texts) who live on an estancia called "la novella." Three sets of lovers (Eterna and the President; The lover—Deunamor—and his anonymous lover; and Maybegenius and Sweetheart) in different settings exemplify or put into practice or reason the so-called concept of “todoamor,"—“totallove"—which overcomes what the world calls death, merely “hiding/ocultación” in Macedonio’s vocabulary. He writes: “I do not believe in the death of those who love nor in the life of those who do not love.”

Thus the only death possible and present in this novel is the academic death of the characters. Critics have suggested that the long process of writing this novel from 1925 until his death in 1952 was Macedonio’s attempt to fight his pain and fear following the untimely death of his wife, Elena de Obieta, in 1920.

The translator, Margaret Schwartz, Assistant Professor of Communication and Media Studies at Fordham University, has done an outstanding job translating Macedonio’s baroque, convoluted prose, complicated language, and invented words, preserving his unique voice. The quality of her translation no doubt comes from her time spent in Argentina prior to and under a Fulbright fellowship in 2004, her first-hand familiarity with living in the literary circles of Buenos Aires, and her meticulous research on the life and work of Macedonio Fernández. This is more meritorious when, in her own words, she is translating “someone who deliberately tangles his words, uses antiquated language, and who writes at the speed of thought, without regard for syntax and punctuation.” But even more so, I might add, because Macedonio Fernández is a genius like Cervantes and Kafka—who not only created their own language but masterfully caused the unpredictable methamorphosis of the genre.

Luis Alberto Ambroggio, a member of the North-American Academy of the Spanish Language, is Writer's Center workshop leader and an internationally known Hispanic-American poet born in Argentina. He is the author of eleven collections of poetry. His poetry and essays have appeared in newspapers, magazines (including Passport, Scholastic, International Poetry Review, and Hispanic Culture Review), poetry anthologies (DC Poets Against the War, Cool Salsa), textbooks (Paisajes, Bridges to Literature, Voices: Breaking Down Barriers) and award-winning electronic collections of Latino Literature (Alexander Street Press). Recently, another Writer's Center workshop leader, Yvette Neisser Moreno, edited his Difficult Beauty: Selected Poems. You can read a review of that book here.

He can be reached at lambroggio@cox.net

The Museum of Eterna’s Novel (The First Good Novel)

(translated from the Spanish by Margaret Schwartz) with a foreword by Adam Thirwell.

Open Letter

Pub Date: February 23, 2010

Reviewed by Luis Alberto Ambroggio

In this extraordinary literary creation, Borges’ mentor, Macedonio Fernández, masters in the reader's playful engagement to games of the word and of the mind beyond literature and metaphysics. One of the great Argentine writers of the twentieth century, Macedonio (as he preferred to be called), wrote this novel (or anti-novel) with an originality and perversity second to none—way ahead of his time and beyond the avant-guard rupture with previous conventions. He redefined the genre and influenced the great literary geniuses among Hispanic-American writers, including Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, Ricardo Piglia, and many others.

“Whoever preceded him might shine in history," Borges wrote, "but they were all rough drafts of Macedonio, imperfect previous versions. To not imitate this canon would have represented incredible negligence.”

The Museum of Eterna’s Novel (The First Good Novel) is structured as a challenge to realism, to logic, and to structure itself, as if the author intended to demolish the sense of fluidity of a normal novel and its aesthetic tendency towards realism and the solemnity of style. Instead, we (the readers) are forced (as well as intelectually seduced) to immerse ourselves in continual digressions and discussions on the roles of authors, readers, critics, characters, theories on genres, etc., as if these topics were objects which are acquired and kept in a Museum. This Museum is also, as Adam Thirlwell writes in the foreword, a “laboratory for investigating whether every philosophical question can be observed through the condition of falling in love.”

Museum starts by offering over 50 prologues with a wide range of themes: mortality and eternity; perspective and the viscitudes of the author (including authorial despair); critics; context; non-existence; and so on. Many of these themes have digressions containing dedications, salutations, and narratives on whether readers should accept or reject a chracter in an elaborate effort to playfully frustrate and challenge.

Following the prologues are twenty chapters concerning a group of characters (some borrowed from other texts) who live on an estancia called "la novella." Three sets of lovers (Eterna and the President; The lover—Deunamor—and his anonymous lover; and Maybegenius and Sweetheart) in different settings exemplify or put into practice or reason the so-called concept of “todoamor,"—“totallove"—which overcomes what the world calls death, merely “hiding/ocultación” in Macedonio’s vocabulary. He writes: “I do not believe in the death of those who love nor in the life of those who do not love.”

Thus the only death possible and present in this novel is the academic death of the characters. Critics have suggested that the long process of writing this novel from 1925 until his death in 1952 was Macedonio’s attempt to fight his pain and fear following the untimely death of his wife, Elena de Obieta, in 1920.

The translator, Margaret Schwartz, Assistant Professor of Communication and Media Studies at Fordham University, has done an outstanding job translating Macedonio’s baroque, convoluted prose, complicated language, and invented words, preserving his unique voice. The quality of her translation no doubt comes from her time spent in Argentina prior to and under a Fulbright fellowship in 2004, her first-hand familiarity with living in the literary circles of Buenos Aires, and her meticulous research on the life and work of Macedonio Fernández. This is more meritorious when, in her own words, she is translating “someone who deliberately tangles his words, uses antiquated language, and who writes at the speed of thought, without regard for syntax and punctuation.” But even more so, I might add, because Macedonio Fernández is a genius like Cervantes and Kafka—who not only created their own language but masterfully caused the unpredictable methamorphosis of the genre.

Luis Alberto Ambroggio, a member of the North-American Academy of the Spanish Language, is Writer's Center workshop leader and an internationally known Hispanic-American poet born in Argentina. He is the author of eleven collections of poetry. His poetry and essays have appeared in newspapers, magazines (including Passport, Scholastic, International Poetry Review, and Hispanic Culture Review), poetry anthologies (DC Poets Against the War, Cool Salsa), textbooks (Paisajes, Bridges to Literature, Voices: Breaking Down Barriers) and award-winning electronic collections of Latino Literature (Alexander Street Press). Recently, another Writer's Center workshop leader, Yvette Neisser Moreno, edited his Difficult Beauty: Selected Poems. You can read a review of that book here.

He can be reached at lambroggio@cox.net

Friday, February 19, 2010

Friday Member News

First off, thanks to our great new receptionist Zachary Fernebok for putting together this new First Person Plural layout. What do you think? The design across the banner is by another great new staff member, publications & communications coordinator Maureen Punte. Incidentally, it's been such a busy day that we've not yet completed the overhaul. That white space up above will soon be fixed.

Note a couple of new blogs FPP is following. The Real Writer and Embarking on a Course of Study.

Second, Story/Stereo tonight. One small adjustment to the schedule. Andrew Beierle will read instead of Steve Fellner (who is ill). J. Robbins and Marianne Villanueva will join him, as scheduled. 8p.m. And it's free!

The new Web site is looking really good (and I mean www.writer.org). We saw the initial designs yesterday and we're all super excited. More on that later.

News flashes: I'd just like to point out this Newshour interview with Writer's Center member James McGrath Morris, author of the new biography Pulitzer: a Life in Politics, Print, and Power.

And check out these great events going on at the Southeast Neighborhood Library in DC all this month--in honor of Black History Month. Tonight, for example, is an Open Mic.

Have a great weekend!

Note a couple of new blogs FPP is following. The Real Writer and Embarking on a Course of Study.

Second, Story/Stereo tonight. One small adjustment to the schedule. Andrew Beierle will read instead of Steve Fellner (who is ill). J. Robbins and Marianne Villanueva will join him, as scheduled. 8p.m. And it's free!

The new Web site is looking really good (and I mean www.writer.org). We saw the initial designs yesterday and we're all super excited. More on that later.

News flashes: I'd just like to point out this Newshour interview with Writer's Center member James McGrath Morris, author of the new biography Pulitzer: a Life in Politics, Print, and Power.

And check out these great events going on at the Southeast Neighborhood Library in DC all this month--in honor of Black History Month. Tonight, for example, is an Open Mic.

Have a great weekend!

Thursday, February 18, 2010

Remembering Lucille Clifton

Poetry lovers were saddened to hear of the recent death of Lucille Clifton, a poet long-active in the community (and native of Buffalo, NY). Merrill Leffler, a poet and editor of Dryad Press, emailed a letter to Grace Cavalieri after her passing, and Grace was moved to forward it to many friends. We’re posting the letter, with Merrill’s permission, for today’s blog entry. Lucille Clifton read at The Writer's Center in 1979. See photo to the left. (This event also featured Tom Jones, The First Washington Poetry Quartet, Linda Pastan, Edward Weismiller, Elisavietta Ritchie, Roland Flint, Robert Zelenka, Sterling Brown, Ann Darr, Henry Taylor, Rod Jellema, Deirdra Baldwin, and Susan Sonde.)

I just turned on my computer and there was your message about Lucille's death. A large woman in more ways that I can say -- I didn't know Lucille well at all, only through her poetry. She took part in a couple of workshops I did at St. Mary's -- we spoke in passing; then there was the Maryland poet laureates fest at UM, and a couple of other times.

You didn't ask but I'll mention this: I first heard Lucille read her poems in the spring of 1969 -- I think it was at GW and I went with Rod [Jellema]because of Carolyn Kizer who may have been instrumental in arranging the reading and perhaps getting the manuscript to Vintage for the book that was to come -- I don't remember. How could I not be taken by the poems themselves and Lucille's presence and voice. They were new! Of course she had a wholly distinctive voice. Not long afterwards, Ann [Slayton] and I left for England, August 1969, for a year at Oxford that turned into three. It must have been sometime in late 1970 that I was in a used bookstore in London and miraculously, it seemed then, happened on Good Times on the shelf. I didn't even know it had been published. What a joy to read the poems I had only heard one time! I wound up writing an essay-review of eight books, "O Children Think about the Good Times" for Dryad 7/8 (1971), opening with Lucille's, then going on to books by Raymond Carver, Robert Mezey, and several other poets. So here's the piece, though again, you didn't ask for it.

"O Children Think About the Good Times"

when I watch you

you wet brown bag of a woman

who used to be the best looking gal in Georgia

used to be called the Georgia Rose

I stand up

through your destruction

I stand up

("Miss Rosie")

Lucille Clifton's Good Times has an energy, which is difficult to describe. There are not many poems, less than forty, all short, and it takes little time to read through. They are still there when you are finished. Very few drift or blur one into another; they press themselves and hearing Mrs. Clifton speak then wakens you again to the realization that poetry, oral poetry, can alter your sensibilities; that words have the power for affecting beyond the moment, that in their vigor and health, they genuinely convey the primacy of the active will. In the midst of an America where whatever side you choose to find yourself, as Louis Simpson writes, "standing against the wall," how is it these poems manage their positiveness? It is not enough to say that they are celebrations. They inhale the city and they inhale the south; they inhale the past and we sense the deep breath of that past in the present; they are the poems of a woman, a daughter, a mother, of a human being in America who is -- inseparably -- black; who is proud and bitter, compassionate and angry, who is a poet, who is all of these roles in one and shrinks from none.

To describe these poems as celebrations is not to imply a poetry of joy; the under-riding pathos negates that. "My Mama moved among the days/ like a dreamwalker in a field":

She got us almost through the high grass

then seemed like she turned around and ran

right back in

right back on in.

So does the sculptural concreteness of daddy:

My daddy's fingers move among the couplers

chipping steel and skin

and if the steel would break

my daddy's fingers might be men again.

The city, the "inner city,' is no place you live simply to survive. Survival is no longer the question: that's been proved.

If i stand in my window

naked in my own house

and press my breasts

against my windowpane

like black birds pushing against glass

because I am somebody

in a New Thing

. . .

let him watch my black body

push against my own glass . . .

I could go on quoting. These poems impact with a power in an exuberant voice -- they are direct and directness is wrought from a language that is, at the same time, simple and sophisticated: from the repetitiveness of endings to the confident handling of metaphors (i.e., "my daddy's fingers"). Mrs. Clifton's poems have that unique expressiveness of a life -- not as it should be lived, not as it is hoped to be lived -- that is being lived. It is an expressiveness that seems the extension, the creation, of self. It is a joy to be able to share.

If you'd like to hear Lucille Clifton reading from her work, click here.

I just turned on my computer and there was your message about Lucille's death. A large woman in more ways that I can say -- I didn't know Lucille well at all, only through her poetry. She took part in a couple of workshops I did at St. Mary's -- we spoke in passing; then there was the Maryland poet laureates fest at UM, and a couple of other times.

You didn't ask but I'll mention this: I first heard Lucille read her poems in the spring of 1969 -- I think it was at GW and I went with Rod [Jellema]because of Carolyn Kizer who may have been instrumental in arranging the reading and perhaps getting the manuscript to Vintage for the book that was to come -- I don't remember. How could I not be taken by the poems themselves and Lucille's presence and voice. They were new! Of course she had a wholly distinctive voice. Not long afterwards, Ann [Slayton] and I left for England, August 1969, for a year at Oxford that turned into three. It must have been sometime in late 1970 that I was in a used bookstore in London and miraculously, it seemed then, happened on Good Times on the shelf. I didn't even know it had been published. What a joy to read the poems I had only heard one time! I wound up writing an essay-review of eight books, "O Children Think about the Good Times" for Dryad 7/8 (1971), opening with Lucille's, then going on to books by Raymond Carver, Robert Mezey, and several other poets. So here's the piece, though again, you didn't ask for it.

"O Children Think About the Good Times"

when I watch you

you wet brown bag of a woman

who used to be the best looking gal in Georgia

used to be called the Georgia Rose

I stand up

through your destruction

I stand up

("Miss Rosie")

Lucille Clifton's Good Times has an energy, which is difficult to describe. There are not many poems, less than forty, all short, and it takes little time to read through. They are still there when you are finished. Very few drift or blur one into another; they press themselves and hearing Mrs. Clifton speak then wakens you again to the realization that poetry, oral poetry, can alter your sensibilities; that words have the power for affecting beyond the moment, that in their vigor and health, they genuinely convey the primacy of the active will. In the midst of an America where whatever side you choose to find yourself, as Louis Simpson writes, "standing against the wall," how is it these poems manage their positiveness? It is not enough to say that they are celebrations. They inhale the city and they inhale the south; they inhale the past and we sense the deep breath of that past in the present; they are the poems of a woman, a daughter, a mother, of a human being in America who is -- inseparably -- black; who is proud and bitter, compassionate and angry, who is a poet, who is all of these roles in one and shrinks from none.

To describe these poems as celebrations is not to imply a poetry of joy; the under-riding pathos negates that. "My Mama moved among the days/ like a dreamwalker in a field":

She got us almost through the high grass

then seemed like she turned around and ran

right back in

right back on in.

So does the sculptural concreteness of daddy:

My daddy's fingers move among the couplers

chipping steel and skin

and if the steel would break

my daddy's fingers might be men again.

The city, the "inner city,' is no place you live simply to survive. Survival is no longer the question: that's been proved.

If i stand in my window

naked in my own house

and press my breasts

against my windowpane

like black birds pushing against glass

because I am somebody

in a New Thing

. . .

let him watch my black body

push against my own glass . . .

I could go on quoting. These poems impact with a power in an exuberant voice -- they are direct and directness is wrought from a language that is, at the same time, simple and sophisticated: from the repetitiveness of endings to the confident handling of metaphors (i.e., "my daddy's fingers"). Mrs. Clifton's poems have that unique expressiveness of a life -- not as it should be lived, not as it is hoped to be lived -- that is being lived. It is an expressiveness that seems the extension, the creation, of self. It is a joy to be able to share.

If you'd like to hear Lucille Clifton reading from her work, click here.

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

Opportunities for Writers

A quick post today to let you know of a couple opportunities for writers. First, as announced here before, Bethesda Magazine and Bethesda Urban Partnership are holding their annual short story/essay contest. The deadline for this is approaching (Feb. 26). For complete guidelines, click here.

And the Santa Fe Writers Project, who has long had a literary awards program, is now branching off to having a screenplay contest. In fact, they're offering both this year. For more information on those contests, click here.

And the Santa Fe Writers Project, who has long had a literary awards program, is now branching off to having a screenplay contest. In fact, they're offering both this year. For more information on those contests, click here.

Monday, February 15, 2010

From the Ashes: Using Words to Inspire Youth

by Jenny Chen

Editor-in-Chief

JJ Express Magazine

I was quite the prolific writer as a kid, filling entire Whole Foods bags with my scribbling about boarding school girls, orphans sent to battle mythical creatures, and detective shorts. Since my efforts were acknowledged by a smattering of youth awards and publications, I aimed my sights higher – my dream was to be published in Cricket Magazine. Cricket is a high-quality literary magazine for children. The late Lloyd Alexander sat on its Advisory Board…this was the real deal.

As a 10-year-old, I sent off a manuscript into the unknown land of New Hampshire to begin what I was sure would be an illustrious career as a writer. Then I waited, and waited, and waited. Nearly a year later, a letter arrived. I opened it up – inside was my unopened manuscript and a rejection letter.

The letter read, “We’re sorry, we don’t publish student work.”

I was crushed.

There had to be some way, I told my brother, for youth to be published alongside adults. I was frustrated that youth work were always relegated to magazines specifically for young people – like Creative Kids – or in the back of a magazine somewhere. There had to be something we had in common.

In taking out the recycling for my mom, it hit me. Change. More specifically, social change. People young and old, rich and poor, were all affected by issues like pollution, discrimination, and poverty. If there’s one thing that all people have in common, it’s the desire to see a better world for us and for our children.

The idea stewed in my mind and didn’t really take hold until I was a junior in high school and I started doing research for my Humanities and Arts Senior Independent Project – on picture books and comics. Comics were a powerful, timeless art form that combined both words and images in an almost alchemical way.

Spurred by this thought, I contacted several artists about my idea. The Managing Editor of New Moon Magazine for Girls at the time, Lacey Louwagie, answered the myriad questions that I had about everything from layout to editing. I enlisted the help of my brother who had the artistic skills I did not possess. We received a $1,000 start-up grant from Youth Venture

And that was how JJ Express Magazine – a quirky little publication that resists categorization – was born. We use comics to inspire youth to create social change.

It isn’t a comic book – because the comics inside are illustrated by artists from all over the world and in all different styles. Within one issue, you can find manga and Dick Tracy style back to back. It obviously isn’t a bread and butter literary magazine. It probably can only be described as an anthology of sorts for children.

True to our founding mission to involve everybody – all ages, all backgrounds, all walks of life, I have had the opportunity to work with artists from Brazil, Vietnam, France, and some just from Maryland. Some are students, some are professionals, and some are just life-long dabblers in the cartoon arts. We’ve received grants and awards from Youth Venture, the Best Buy Foundation, and the Disney Minnie Grant Foundation. We currently circulate magazines all over Montgomery County.

Today, I stay up late at night listening to the outside chatter of college students die down as the drift off sleepily to bed while I layout the latest issue, chat with an artist in France, and answer mail from readers. I love every second of it.

And to think – all this came from the stubborn dreams of a young girl who just wanted to be a writer.

Jenny Chen is currently a freshman at Colby College.

Editor-in-Chief

JJ Express Magazine

I was quite the prolific writer as a kid, filling entire Whole Foods bags with my scribbling about boarding school girls, orphans sent to battle mythical creatures, and detective shorts. Since my efforts were acknowledged by a smattering of youth awards and publications, I aimed my sights higher – my dream was to be published in Cricket Magazine. Cricket is a high-quality literary magazine for children. The late Lloyd Alexander sat on its Advisory Board…this was the real deal.

As a 10-year-old, I sent off a manuscript into the unknown land of New Hampshire to begin what I was sure would be an illustrious career as a writer. Then I waited, and waited, and waited. Nearly a year later, a letter arrived. I opened it up – inside was my unopened manuscript and a rejection letter.

The letter read, “We’re sorry, we don’t publish student work.”

I was crushed.

There had to be some way, I told my brother, for youth to be published alongside adults. I was frustrated that youth work were always relegated to magazines specifically for young people – like Creative Kids – or in the back of a magazine somewhere. There had to be something we had in common.

In taking out the recycling for my mom, it hit me. Change. More specifically, social change. People young and old, rich and poor, were all affected by issues like pollution, discrimination, and poverty. If there’s one thing that all people have in common, it’s the desire to see a better world for us and for our children.

The idea stewed in my mind and didn’t really take hold until I was a junior in high school and I started doing research for my Humanities and Arts Senior Independent Project – on picture books and comics. Comics were a powerful, timeless art form that combined both words and images in an almost alchemical way.

Spurred by this thought, I contacted several artists about my idea. The Managing Editor of New Moon Magazine for Girls at the time, Lacey Louwagie, answered the myriad questions that I had about everything from layout to editing. I enlisted the help of my brother who had the artistic skills I did not possess. We received a $1,000 start-up grant from Youth Venture

And that was how JJ Express Magazine – a quirky little publication that resists categorization – was born. We use comics to inspire youth to create social change.

It isn’t a comic book – because the comics inside are illustrated by artists from all over the world and in all different styles. Within one issue, you can find manga and Dick Tracy style back to back. It obviously isn’t a bread and butter literary magazine. It probably can only be described as an anthology of sorts for children.

True to our founding mission to involve everybody – all ages, all backgrounds, all walks of life, I have had the opportunity to work with artists from Brazil, Vietnam, France, and some just from Maryland. Some are students, some are professionals, and some are just life-long dabblers in the cartoon arts. We’ve received grants and awards from Youth Venture, the Best Buy Foundation, and the Disney Minnie Grant Foundation. We currently circulate magazines all over Montgomery County.

Today, I stay up late at night listening to the outside chatter of college students die down as the drift off sleepily to bed while I layout the latest issue, chat with an artist in France, and answer mail from readers. I love every second of it.

And to think – all this came from the stubborn dreams of a young girl who just wanted to be a writer.

Jenny Chen is currently a freshman at Colby College.

Monday Review: Towers of Gold

Towers of Gold: How One Jewish Immigrant Named Isaias Hellman Created California

By Frances Dinkelspiel

376 pages (paperback)

St. Martin’s Griffin, New York

$16.99

Published January 2010

Reviewed by Linda Singer

With sumptuous description and meticulous detail, Frances Dinkelspiel traces the exciting history of California through the biography of her great-great grandfather, Isaias Hellman. Born in Reckendorf, Bavaria in 1842, Isaias’s multi-layered life allows us a close view of the pioneers whose skilled determination and personal risk-taking were critical to the early development and formative years of the State of California.

Because they are Jews, Isaias and his younger brother Herman leave Reckendorf seeking refuge from European persecution, first in Los Angeles and later in San Francisco, where they find comfort and safety in places where no attention is given to religion. Both brothers become large benefactors to synagogues in northern and southern California and continue throughout their lives to be socially, economically, and politically involved organizing and acting as leaders of these newly founded Jewish communities.

Between the years 1859 when a penniless Isaias Hellman arrives in Los Angeles and 1910 when he becomes, as Dinkelspiel puts it, “a major investor and promoter of at least eight industries... banking, transportation, education, land development, water, electricity, oil, and wine...,” Isaias amasses a fortune worth approximately $38 billion in today’s currency. The intricacies of his numerous business dealings and the diversity of his friends and financial partners leaves one’s head reeling.

Personal as well as public image was very important to Isaias Hellman. More importantly, he was a family man with high principles and enormous integrity. Numerous times, and often at serious personal risk, he stood up to his foes as well as his friends to stabilize a vulnerable infant economy. Repeatedly he contributed huge sums of his own fortune to bolster, improve, protect, and grow California’s economy while mobilizing his peers to do likewise.

How monumental the task undertaken by Dinkelspiel to assemble overwhelming amounts of data accumulated from stacks of letters, diaries, and cartons to reconstruct this larger than life man.

At times it is a bit difficult to keep all the “players” straight. Their vast fortunes, complex business transactions, frequently changing personal interactions, and alliances are nearly impossible to grasp and hold onto as one weaves through the very fabric of early California politics and economics. Nonetheless, this is an exceptionally well-documented and eloquently written biography of a key figure in the history of the state; a superb read, especially if California is near and dear to your heart.

Find the book here.

By Frances Dinkelspiel

376 pages (paperback)

St. Martin’s Griffin, New York

$16.99

Published January 2010

Reviewed by Linda Singer

With sumptuous description and meticulous detail, Frances Dinkelspiel traces the exciting history of California through the biography of her great-great grandfather, Isaias Hellman. Born in Reckendorf, Bavaria in 1842, Isaias’s multi-layered life allows us a close view of the pioneers whose skilled determination and personal risk-taking were critical to the early development and formative years of the State of California.

Because they are Jews, Isaias and his younger brother Herman leave Reckendorf seeking refuge from European persecution, first in Los Angeles and later in San Francisco, where they find comfort and safety in places where no attention is given to religion. Both brothers become large benefactors to synagogues in northern and southern California and continue throughout their lives to be socially, economically, and politically involved organizing and acting as leaders of these newly founded Jewish communities.

Between the years 1859 when a penniless Isaias Hellman arrives in Los Angeles and 1910 when he becomes, as Dinkelspiel puts it, “a major investor and promoter of at least eight industries... banking, transportation, education, land development, water, electricity, oil, and wine...,” Isaias amasses a fortune worth approximately $38 billion in today’s currency. The intricacies of his numerous business dealings and the diversity of his friends and financial partners leaves one’s head reeling.

Personal as well as public image was very important to Isaias Hellman. More importantly, he was a family man with high principles and enormous integrity. Numerous times, and often at serious personal risk, he stood up to his foes as well as his friends to stabilize a vulnerable infant economy. Repeatedly he contributed huge sums of his own fortune to bolster, improve, protect, and grow California’s economy while mobilizing his peers to do likewise.

How monumental the task undertaken by Dinkelspiel to assemble overwhelming amounts of data accumulated from stacks of letters, diaries, and cartons to reconstruct this larger than life man.

At times it is a bit difficult to keep all the “players” straight. Their vast fortunes, complex business transactions, frequently changing personal interactions, and alliances are nearly impossible to grasp and hold onto as one weaves through the very fabric of early California politics and economics. Nonetheless, this is an exceptionally well-documented and eloquently written biography of a key figure in the history of the state; a superb read, especially if California is near and dear to your heart.

Find the book here.

Friday, February 12, 2010

Workshop Leader Sue Ellen Thompson Wins Maryland Author Award

Congratulations to workshop leader Sue Ellen Thompson. Her next workshop at The Writer's Center will be Syntax as Strategy beginning on March 7. Here's the word from the official release:

Sue Ellen Thompson of Oxford, Maryland has been selected to receive the 2010 Maryland Author Award from the Maryland Library Association. The award is presented annually to recognize a Maryland author for his or her “body of work”.

Sue Ellen Thompson is a graduate of Middlebury College, Vermont (B.A.) and The Bread Loaf School of English (M.A.). Her first book of poems, This Body of Silk, was awarded the 1986 Samuel French Morse Prize. A second volume, The Wedding Boat, was published in 1995 and a third, The Leaving: New and Selected Poems, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 2001. A fourth volume, The Golden Hour, was also nominated for a Pulitzer in 2006. Her work has been included in the Best American Poetry series, read on National Public Radio, and featured in U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser’s nationally syndicated newspaper column. She recently edited The Autumn House Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry.