By Jenny J. Chen

At the

Creative Nonfiction Conference I went to recently in Pittsburgh, Kristin

Kovacic, author of House of Women, said,

“You must stick the ending.”

As a

reporter and creative nonfiction writer, I agree. Endings are so incredibly

important, not only because they are the final note of a piece, but also

because they give it a reason for being. A good ending should reverberate like

a gong within the reader’s soul long after they’ve put the piece down.

Of

course, crafting such an ending can be tricky. What defines a good ending? At

the most elementary level, an ending should drive home the point without being

too obvious (but what’s too obvious?). It should arise organically out of the

material that came before so that it feels earned and “right.” There are also

many great endings that break all the rules. I set out to examine some of my

favorite endings in an expedition to figure out what makes them so powerful. Warning:

obviously, there are spoilers here.

Steroid Nation

By Shaun Assael

By Shaun Assael

This

book follows the rise and fall of Dan Duchaine, “godfather” of the steroid

movement in the U.S., as he deals in steroids and accidentally ruins the lives

of several girlfriends along the way. He finally succumbs to cancer at the age

of 48. Duchaine is the author of the Underground

Steroid Handbook, which catapulted steroids into mainstream athletic

communities. Assael expertly crafts a tale that is both riveting and

meticulously researched.

The

ending is no less spectacular. In the last chapter, Assael concludes by saying the

steroid community Duchaine built has grown uncontrollably to become a “steroid

nation” and then a “steroid world.” The last paragraph reads:

“In

1981, Dan Duchaine had a simple idea for a book that would galvanize the new

world he wanted to create. The words he helped write in the Underground Steroid Handbook sound as

urgent today as they did then: ‘Although we will antagonize many of you, we

thought we should tell the truth about steroids.’”

The

“truth” in the original context is that steroids are effective and safe if used

in a knowledgeable way. Assael has co-opted Duchaine’s words to drive home the

message that his book tells the

“truth”—steroids ruin lives and Duchaine’s in particular. If you can find a way

to circle back to a key, multi-dimensional theme in your piece, do it. It can be difficult to find

something that fits so perfectly, so it is also important to note other

features of this ending:

- It circles back to the beginning of the story but doesn’t “bookend” it. Most endings do this and it gives endings a feeling of completion—that they’re arising organically from previous material.

- It drives home the theme that Assael has been carrying throughout the book. Note that the theme is different from the argument. Many people will say that the ending should emphasize the take-home message, but the technique can be crude because it lacks subtlety and bangs the reader over the head with a take away.

- I can imagine Assael telling his buddies over a drink that he wanted to write this book to tell people the truth about steroids. And so he leaves us with that thought.

Welcome to Dog

World!

By Blair Braverman

By Blair Braverman

Blair

Braverman’s esasay for The Atavist is

one of the most amazing personal essays I have read in a long time. Braverman

details a claustrophobic experience working at a luxury tourist spot called Dog

World in a remote part of Alaska. Braverman is in charge of taking the tourists

out on mushing expeditions. Behind the scenes, however, she and her fellow

female musher have to endure bullying and sexual harassment from their male

co-workers.

In the

middle of the story, news breaks that the tourists are stranded in Dog World. It becomes the staff’s job to keep

the tourists calm and happy with bright smiles and endless rounds of Parcheesi.

At the end of the piece, when the helicopters finally arrive, Braverman writes:

“…in

the moment, mid-rescue, the dogs were in a frenzy, yelping and leaping on their

chains, and the pilots were shouting, and the noise of the rotors drowned

everything else.

I

remember this, though: When the helicopters first came into view, all of the

guests, as if by instinct, raised their arms, reaching. And without realizing

it, I did, too.”

This

ending left me breathless. It spiraled organically from the central tensions

running through the piece: Braverman’s desire to get out of Dog World and the

disconnect between the tourists’ experiences and the staff’s experiences.

Not

all endings need to include commentary (in fact, the best ones don’t), and this

is an example of how a scene can do the job in a much more subtle way. Avoid being

too heavy-handed with this approach by carefully examining the scene for

details and images that echo your themes or tensions, instead of trying to

force a scene into that role. I would also be remiss if I didn’t point out that

Braverman has a book coming out called Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube. Check it out—you won’t

be disappointed.

The Story of a Year

By David James Poissant

By David James Poissant

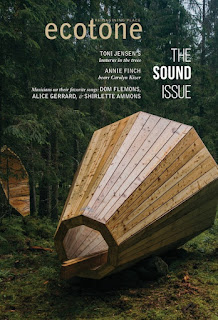

David

James Poissant’s essay, published in the spring 2016 issue of Ecotone, details in sparse, beautiful

language, the struggles of the author’s family move to Florida. Throughout the

course of the piece, Poissant reveals both big and small events in a

matter-of-fact way. The family buys multiple fish (as they die one after the

other); his little girls grow up; an armadillo makes a nest under their house;

and the mother is diagnosed with breast cancer and survives treatment. There’s

a strong sense of the march of time. In the last lines, he writes:

“And

then it’s toothbrush time and pee time and prayer time and story time.

And

the children are nestled all snug in their beds.

And

before long—but let’s not get to before long. Before long will come soon

enough.

And

under the house, the armadillo digs and digs.”

The

return of the armadillo not only echoes earlier material but it also conveys

the central theme of the piece, which is, simply, life goes on. It even matches

that theme in rhythm and tone—“digs and digs” suggests both the continual and

often repetitive nature of daily life. As with Assael’s book, this ending

reflects the theme of the piece, not

necessarily the take-home message.

It may

seem blasphemous for a blog post on endings not to have a great ending lined

up, but good endings take time. They need to marinate in musings before they

emerge. I hope that, at the very least, this post has given you something to

muse about.

Jenny J. Chen is a science and health reporter

based in D.C. Her work has appeared in The

Atlantic, NYTimes.com, NPR, Washington Post, and others. She moonlights as

a poet and creative nonfiction writer.

No comments:

Post a Comment